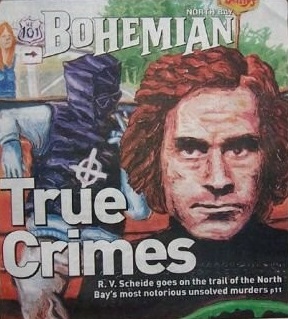

Killers Club Investigating the North Bay's most notorious unsolved murders with the cybersleuths at ZodiacKiller.com 15th Anniversary Flashback Story: |

|||||

By R.V. Scheide North Bay Bohemian On the Monday before Christmas, Tom Voigt, Ed Neil and Angie Avey will travel to Lake Herman Road on the eastern outskirts of Vallejo to a remote gravel turnout where an unknown assailant shot and killed a high school couple exactly 36 years ago. That attack was just the beginning of a murderous rampage that in the coming months and years would terrify Bay Area residents, capture national and international media attention and defy homicide investigators to this day. Voigt was just one year old when the murderer who became known as "the Zodiac" first struck. Today, the lanky, bespectacled 37-year-old is the founder of ZodiacKiller.com, a website dedicated to solving the most infamous and longest-running murder mystery in Northern California, one that remains unsolved. Voigt, a website designer by trade, started the Zodiac site in 1998 after a reenactment of the murders on Unsolved Mysteries piqued his interest. He even relocated from Portland to San Francisco in order to be closer to the Zodiac crime scenes. Massage therapist Ed Neil, 39, and office manager Angie Avey, 31--from Napa and Calistoga respectively--became fascinated with the Zodiac after absorbing former San Francisco Chronicle political cartoonist Robert Graysmith's popularized account of the murders, the 1986 true-crime book Zodiac, which for many years was considered the definitive tome on the topic. Their fascination with the case led them to ZodiacKiller.com, where each separately struck up an e-mail friendship with Voigt. These days, the threesome spend their spare time pouring over court, police and newspaper records and scouting crime scenes as a hobby along the back roads of the North Bay, where many of the Zodiac's known and suspected victims were murdered or dumped, seeking clues that might advance movement in a case that has otherwise stalled, if only because of old age. They are on an audacious quest: to discover the identity of a killer whose name has eluded the nation's sharpest investigative minds for over three decades. And despite the case's age, the trio by no means hunt alone. Interest in the Zodiac remains high around the world; Voigt's website averages as many as 1.5 million hits per month. More than three decades after the killer first struck, his murderous acts continue to exert a tremendous pull on the popular imagination, having been the subject of numerous books, TV series and movies. Family members of the Zodiac's victims have e-mailed Voigt to thank him for keeping the investigation going. Amateur sleuths from around the world send him tips and engage in chat-room discussions concerning their favored suspects. Infamous names occasionally crop up: if verified, one tip Voigt received places executed serial killer Ted Bundy in Sonoma County between 1972 and 1973, when the bodies of seven young women were discovered in rural areas just outside of Santa Rosa in a killing spree now known as the Santa Rosa Hitchhiker Murders. At the time, Zodiac hysteria was at its height, and the Sonoma County Sheriff's Department considered the elusive serial killer a prime suspect. Most of the young women had been hitchhiking along or near Highway 101. The killer--or killers--preferred strangling the victim and discarding her nude body in rural roadside gullies like so much refuse. The victims ranged from 12 to 22 in age; some were sexually assaulted. Today, the murderer of those seven young women remains a matter of conjecture, not fact. The case is unsolved. "It's all speculation," explains John Hess, a retired Sonoma County Sheriff's detective who helped lead the investigation of the Hitchhiker Murders. Hess, now in his 70s, worked dozens of homicide cases during his career, but still recalls the names of each of the seven young women and where they were found. "We could never come up with anything definite," he says. "It's hard to say what happened." As uncomfortable as that may sound to survivors, it's the essence of good mystery--the nagging doubt that for Voigt, Neil and Avey is an irresistible force drawing them back to a more innocent time, when couples parked in lovers' lanes and young women hitchhiked along the Highway 101 corridor without fear, and no one had ever heard of the Zodiac killer or Ted Bundy. On July 4, 1969, seven months after slaying the high school couple on Vallejo's Lake Herman Road, the Zodiac struck a second time, shooting and killing a 22-year-old woman and seriously injuring a 19-year-old man who were romantically parked at the secluded Blue Rock Springs Park outside Vallejo, not far from the scene of the first crime. After the attack, the killer brazenly called the Vallejo Police Department from a payphone just blocks away from the station to inform them of the crime. Less than a month later, the Vallejo Times-Herald, the San Francisco Chronicle and the San Francisco Examiner each received an ominous letter. "Dear editor," began the hand-printed missive, replete with numerous misspellings and punctuation errors. "This is the murderer of the 2 teenagers last Christmass at Lake Herman & the girl on the 4th of July near the golf course. To prove I killed them I shall state some facts which only I & the police know." Indeed, a list of facts known only to the police and the killer was listed, adding veracity to the letter. On each letter's back, the killer carefully constructed an intricate cryptogram--each newspaper receiving one-third of the puzzle--that he promised would reveal his true identity if solved. He demanded that the editors of the three papers publish the cryptogram on their front pages the following Friday, or, he promised, he would "cruise around all weekend killing lone people in the night." After consulting with police, the newspapers decided to publish the cryptogram. A Bay Area couple managed to solve the complex puzzle, and the result was anything but encouraging. "I like killing people because it is so much fun," the decoded message read. "It is more fun than killing wild game in the forrest because man is the most dangeroue anamal of all to kill." The cryptogram offered no clue to the killer's true identity, as promised. However, in his next letter to the Times-Herald, received Aug. 7, 1969, he used his adopted pseudonym for the first time. "Dear editor," the letter began. "This is the Zodiac speaking." Once again, the writer listed details from the crime scenes that only the killer could know. Explaining how he'd fastened a flashlight to his gun barrel to target his victims at night, he wrote, "When taped to a gun barrel, the bullet will strike exactly in the center of the black dot in the light. All I had to do was spray them." In their riveting 2002 study of the Zodiac's communications with news media and the police, This Is the Zodiac Speaking, authors Michael Kelleher and Sonoma State University psychology professor Dr. David Van Nuys deconstruct the letters in order to construct a profile of the killer. "What does the use of the article 'the' add to the meaning or intent of the message?" writes Van Nuys. "I believe it is an attempt to add importance to the writer. This seems to fit with the writer's obvious sense of his grandiosity. The writer refers to himself as not merely 'Zodiac.' Rather, he is 'the Zodiac.'" Kelleher, who spent part of his boyhood in Guernewood Park and once taught criminology courses at SSU, writes that the first letters mark the beginning of the killer's deadly evolution: "The new element in Zodiac's evolution into the most enigmatic serial killer in California's history was simple and inspired: he would confront, embarrass and intimidate the most dangerous prey--his police adversaries." The Zodiac indeed was an enigmatic serial killer. Most repeat murderers take great pains to cover their tracks and avoid contact with the authorities. With the Zodiac, police were confronted with a psychopath who openly bragged about his exploits and taunted investigators in the local newspapers. With the first letters, the Zodiac nightmare had truly begun. On Sept. 27, 1969, the Zodiac struck again, this time in broad daylight. Creeping up on a couple picnicking on a finger of land jutting out into remote Lake Berryessa, roughly a half-hour drive from Vallejo, the killer, brandishing a pistol and dressed in a handmade black executioner's hood, hogtied his victims with white clothesline and viciously stabbed them. Then, in the same handwriting as the letters, he traced his conquest in the dust on his victims' car door. Exactly two weeks later, he struck again, shooting San Francisco cab driver Paul Stine point-blank in the head in the city's Pacific Heights district and narrowly avoiding police capture by fleeing through the Presidio. To prove he was the culprit, the Zodiac mailed a bloody swatch of Stine's shirt to the Chronicle three days later along with another letter. This time he threatened to attack a school bus. "Just shoot out the front tire & then pick off the kiddies as they come bouncing out," he wrote. Consider now the jagged cultural mosaic the Zodiac quite purposefully inserted himself into, circa 1969: the recent assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy; the Manson Family's bloody rampage in the Malibu canyons; nationwide student protests against the Vietnam War; and now a murderer without a conscience randomly selecting victims, killing freely at will and taking the time to offer the authorities a critique of their impotence that was published in every major Northern California newspaper. Say you would not be afraid. Or, if you're old enough to remember the Zodiac killer, say you were afraid. The school-bus threat, published in local newspapers, sent the Bay Area into a frenzy. Patrol cars escorted school buses on their routes. The Zodiac continued taunting police through letters written to the Chronicle; police responded by lashing out at the killer in newspaper stories about the crimes. In the year that followed the cab driver's murder, the Chronicle published 16 front-page stories on the Zodiac. Perhaps the most disturbing letter sent to the Chronicle by the Zodiac came on Nov. 8, 1969. "I have grown rather angry with police for their telling lies about me," he wrote. "So I shall change the way the collecting of slaves. I shall no longer announce to anyone. They shall look like routine robberies, killings of anger & and a few fake accidents, etc." The letter was signed with his by now familiar symbol, the circle with crosshairs, the same thing seen when looking through a high-powered rifle's scope. "Collecting of slaves" was the concept the Zodiac used to define his grim, murderous project. In letters he would continue to send to newspapers through 1978, he claimed as many as 37 victims. However, it's not clear that the Zodiac killed anyone after he shot the San Francisco cab driver. In This Is the Zodiac Speaking, Kelleher and Van Nuys fix the number of "known" Zodiac victims at seven--the five people murdered and two people injured in the attacks in Vallejo, Lake Berryessa and San Francisco. The relatively low body count may come as a surprise to readers of Zodiac Unmasked, Robert Graysmith's 2002 follow-up to Zodiac. Graysmith makes what initially appears to be a convincing argument that the Zodiac killed far more than five people during the course of his diabolical career, and includes the seven Santa Rosa Hitchhiker Murders in his total. He even goes so far as to "unmask" Zodiac, claiming him to be Arthur Leigh Allen, a longtime suspect in the case who lived in Vallejo and Santa Rosa, and died of natural causes in 1991. If Graysmith's written accounts describing Allen can be trusted, there's no doubt Allen was an extremely twisted individual with many of the attributes of a textbook serial killer: a history of animal torture; a conviction for child molestation; friends, relatives and therapists who were convinced he was the Zodiac; and a far too detailed knowledge of the case when questioned by police in his Santa Rosa trailer. He even owned an expensive Swiss watch manufactured by Zodiac, whose corporate symbol is a circle with crosshairs. The Zodiac, whoever he was, has been thought to have taken his moniker from this brand of watch. But Allen, who has been dead for 13 years, was never charged with any of the murders, and the mystery remains unresolved. Interestingly, in Suspect Zero, a novel based on the Santa Rosa Hitchhiker Murders written prior to This Is the Zodiac Speaking, Kelleher creates a fictional killer who very much resembles Arthur Leigh Allen. Yet in Kelleher's Zodiac Speaking, Allen is dismissed as a suspect in both the Zodiac and the Hitchhiker Murders. When reached by phone at his Washington state home near Mt. St. Helens, Kelleher explained the differences between the two books. "Never ask a writer to tell you the truth," he laughs when asked about the resemblance of the fictional villain presented in Suspect Zero to Arthur Leigh Allen. "All writers are nuts, it just comes with the territory. "The consensus among the Sonoma County Sheriff's Department is that the Zodiac was not involved in [the Hitchhiker Murders]," he continues, adding that getting information out of the department is difficult, "because they're super-sensitive to the unsolved nature of the murders and the fact that many of the relatives still live there." Allen's name is mentioned only once in This Is the Zodiac Speaking. "One of the most seriously considered suspects in the case was Arthur Leigh Allen, who many were absolutely convinced was the fugitive killer," Kelleher writes. "However, Allen was eventually eliminated as a suspect when his fingerprints failed to match those discovered on Paul Stine's cab." Allen also passed a polygraph examination, and six months after Zodiac Unmasked was published in April of 2002, DNA test results on a stamp from one of the Zodiac's letters failed to match Allen's. "Allen was essentially cleared through DNA testing," Voigt says, yet he and Neil still consider Allen a Zodiac suspect, at least for the so-called known killings, if not the Santa Rosa Hitchhiker Murders. In the not-so-distant past, investigators were convinced that the killers were one and the same. In 1975, Sonoma County Sheriff Don Striepeke and Sgt. Butch Carstedt still considered the Zodiac killer a prime suspect in the Hitchhiker Murders. Inviting newspapers from around the state to a Santa Rosa press conference, Striepeke reported that 30 to 40 young women had been recently murdered in six Western states, including Washington, Idaho, Utah, Colorado and California. Furthermore, there were amazing similarities between the cases. All of the victims had been young, attractive women. When laid out on a map, the killer's path resembled a giant sideways "Z" covering the Western United States. The murders could all be the work of the same killer, Striepeke and Carstedt suggested, and the most likely suspect was the Zodiac. At the time, they had no way of knowing that one man was indeed responsible for nearly all of the murders on the northern part of the "Z," located outside of California. That man was Ted Bundy. It's not too difficult to imagine Tom Voigt's excitement when he received an e-mail in 2002 from a woman named Deborah who now lives in the Midwest and claims that during the time of the Hitchhiker Murders she worked at a now-defunct Sonoma County manufacturing company called Electro Vector located in Forestville. Voigt was already familiar with the late Streipeke's theory, thanks to Neil's penchant for tireless newspaper research. He already knew that almost all of the victims on the northern part of Striepeke's "Z" had been attributed to Ted Bundy. And here was Deborah claiming that, for several months in 1972, working right beside her at Electro Vector, looking precisely like the mug shot that by 1976 would be plastered all over national TV, was none other than Ted Bundy. If there is any serial killer who rivals the Zodiac in the public's imagination, it's Bundy. Between 1972 and 1978, he cut a bloody swathe of murder and mayhem through Washington, Utah, Colorado and Florida. His known victims, all young women, number more than 30; he is suspected in dozens of more unsolved murders. When the handsome, charming law student, after successful escapes from jails in Utah and Colorado, was finally apprehended in Florida in 1978, he was asked to estimate how many women he had killed--one figure, two figures or three figures? Bundy held up three fingers, according to authors Stephen Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth's 1983 book The Only Living Witness. Michaud and Aynesworth interviewed Bundy on the Florida State Penitentiary's death row, where he was awaiting execution for killing two college co-eds and a 12-year-old girl in that state. In addition to interviewing Bundy, the authors traced the killer's footsteps across the United States while his trail was still relatively warm. The path led them to Northern California, where Bundy attended classes at Stanford University in Palo Alto in 1968 before dropping out. The only other evidence the authors could find placing Bundy in the state was a 1973 flight from Seattle to San Francisco. Bundy had flown down to reconcile with a former girlfriend, a San Francisco socialite who had dumped him after he washed out at Stanford. Bundy was able to charm her once again, and the couple became engaged. Then Bundy flew back to Seattle and dumped her. Not long after that, young women began disappearing in the Seattle area. In other books written about the case, most notably Anne Rule's Stranger Beside Me (1980), Bundy's failed Northern California relationship is seen as a possible catalyst for the murderous rampage that ensued. Bundy chose victims who resembled his former girlfriend, his ideal: young, pretty college co-eds with long hair parted down the middle, as was the fashion of the time. When photographs of Bundy's known victims are placed side-by-side with pictures of the Santa Rosa Hitchhiker Murder victims, it's as if they all could be sisters. That's why the mystery that remains even after Bundy's 1989 execution is whether the killing started in 1973 or sometime earlier. Dr. Robert Keppel, who led the Bundy investigation in Seattle and has since gone on to become one of the world's foremost experts on serial-killer investigation, has long believed Bundy started much sooner than 1973. Keppel, now president of the Institute for Forensics at Sam Houston University in Huntsville, Texas, spent hours interviewing Bundy in prison, right up until the very end, when the serial killer took his seat in the electric chair infamously called "Old Sparky." As detailed in the 1995 book The Riverman, co-written by Keppel and William Birnes, Bundy promised to reveal the location of all his victims in an effort to stay his execution. Investigators from a half-dozen Western states, including one from Sonoma County, flocked to Florida. True to form, Bundy gave investigators virtually nothing. Nevertheless, Keppel remains convinced that Bundy is a viable suspect for at least some of the Santa Rosa Hitchhiker Murders. Could Bundy really have been the killer? "Oh, it's definitely possible," Keppel responds by phone from his university office. "Who else would have done something like that? We wanted to talk to Bundy about these before the execution." After the execution, Keppel met with Sonoma County Sheriff's Lt. Mike Brown and others familiar with the Hitchhiker Murders to compare notes. Bundy was an avid driver, and covered as much as 600 miles a day during the commission of his crimes. Keppel had obtained virtually all of Bundy's credit card records, making it possible to pin down the killer's location on various dates. "We did a lot of comparing of notes, but we could never hook him," Keppel says. "We couldn't prove that he was on those [Northern California] roads--but we couldn't prove that he wasn't, either." Over the years, Keppel has continued to be amazed at the interest otherwise ordinary people have in serial-murder cases. Although he never directly investigated the Zodiac killings, he's received hundreds of phone calls about the case over the years. In that sense, he doesn't find the existence of ZodiacKiller.com all that odd. "It's amazing to me how there are enthusiasts who get hooked on it; my students get hooked on it," he says. "Most of them are female. I think there's a safety factor involved, they want to know what mistakes the women made to get captured." Yet still, even after Bundy's monstrosities were revealed, some female students continue to have an unhealthy interest in the killer. "He was good looking, wanted to be a lawyer, smooth talking. People are looking out for safety, but at the same time, they like the way the guy looked." Informed about ZodiacKiller.com's Electro Vector tip, Keppel is skeptical. "We never had any evidence whatsoever that Bundy worked in the place you describe," he says. "It's more logical that he made trips to Palo Alto to visit his girlfriend at the time. No way was he working down there." In This Is the Zodiac Speaking, retired Sonoma County Sheriff's Capt. Mike Brown tells Kelleher that Bundy remains a suspect in at least two or three of the Santa Rosa Hitchhiker Murders. "I have one source close to the investigation who likes Bundy for the crime," Kelleher says. "That was his one-beer opinion. His six-beer opinion was, 'I don't know who the fuck did it.'" Kelleher, who places Bundy low on the hitchhiker suspect list, is also skeptical of the Elector Vector tip. He and Voigt have exchanged e-mails, and the successful crime writer finds the ZodiacKiller.com website interesting and sometimes even useful. "If that tip turns out to be substantive, I'd be more inclined to take a look at it," Kelleher says. "[Voigt] gets sent some incredible bullshit, but every once in a while he comes up with a real gem." On an overcast November afternoon, Voigt, Neil and Avey stand outside a chain link fence surrounding a gray, dilapidated industrial warehouse complex near downtown Forestville. A faded wooden sign hanging on the fence still reads "Electro Vector." Like the search for the hitchhiker murderer, the buildings have lain dormant for decades. But just seeing the business mentioned in the e-mail tip is encouraging. Voigt, who has never really been all that interested in Bundy, is excited. "I'm in it for the mystery," he says. "I'm not really interested in guys who've been caught. But if Bundy lived here for even three months, that's 50 or more unsolved murders at least. It would be the biggest unsolved murder case in years." For the time being, the Electro Vector tip remains unproven. But in one of those strange coincidences that seem to hover around serial-killer cases like bees around a hive, it's just a short 10-minute ride from Forestville to the Redwood Empire Ice Arena, where the two 12-year-old girls who were the first victims of the Santa Rosa Hitchhiker Murders were last seen in February 1972. Voigt, Neil and Avey call such coincidences "zynchronicities." Case in point: the circular window with crosshairs in the Charles M. Schulz Museum next to the skating rink resembles the Zodiac's famous symbol exactly. Inside the skating rink, z's are everywhere, the z in the Zamboni machine cleaning the ice, the z in "Peanuts" cartoonist Charles Schulz's surname. "Ice skating is an inherently dangerous sport, all skaters assume their own risk and injury," states a plaque on the wall. Zynchronicity is in the air. It's still in the air as the threesome drive up Calistoga Road, past the summit where the Hitchhiker Murderer's fifth victim, a 13-year-old girl, was found dumped in November 1972. The next stop is a heavily wooded area off Franz Valley Road, where the skeletal remains of the two girls last seen at the skating rink were found in December 1972, 10 months after they had disappeared. The body count was up to five by then, and local law-enforcement officials openly proclaimed they had a serial killer on their hands. As Keppel notes in his 2003 textbook The Psychology of Serial Killer Investigations, making such public admissions is by no means easy for police departments, particularly those without the resources to fund the type of robust investigation required to catch a serial killer. Because the serial killer generally operates alone and chooses strangers for victims, he is more difficult to detect. Often, Keppel notes, police are placed in the uncomfortable position of waiting for the killer to strike again in order to collect new evidence. Two more bodies turned up the following year in Santa Rosa. Then the killings stopped. The investigation, however, continued for years. "As I recall, it was an intensive investigation," says John Hess, the retired Sonoma County Sheriff's detective who personally investigated all of the Hitchhiker Murder crime scenes. Investigators were sent to other jurisdictions to compare similar crimes. "We had five or six detectives working on the cases. We worked them all as long as we could, as long as we had leads." Although the Sonoma County Sheriff's department still considers the case open, it has advanced little in recent years. Knowing that someone got away with the murder of seven young women isn't an easy thing for most law-enforcement officials to accept. "You're always frustrated, because you're committed to solving crimes, especially the murders, the more heinous crimes," says Hess. "You just the do the best you can do, and if you're satisfied that you did your best, you have to turn it over to God." Case Closed? Last April, the San Francisco Police Department announced it was closing the Zodiac investigation. Most people probably read about it in the Chronicle, but Voigt got the story first and posted it on ZodiacKiller.com a week before it hit the mainstream papers. The website has become, in Neil's words, "the center of the Zodiac universe," and both he and Voigt have consulted with various true-crime television series and are even the subject of a European documentary film. Like most web-based communities, those who frequent ZodiacKiller.com share a common, albeit somewhat unusual interest: in their case, solving one of northern California's oldest mysteries. If Voigt, Neil and Avey are successful at cracking either the Zodiac or Hitchhiker Murders, it will be a first, and that's what keeps their juices flowing, no matter how unlikely it may be. "The problem is, it's never been done," says Keppel, who's investigated and consulted on more than 50 serial-killer investigations, including Ted Bundy, the Atlanta Child Murders and Seattle's Green River Murders. "I've never heard of a cold case being solved by someone who just has an avid interest in it." Such talk does not deter Vogt, Neil and Avey. After visiting the Franz Valley Road crime scene, they drive to the Santa Rosa cemetery where the two 12-year-olds, the first victims of the Santa Rosa Hitchhiker Murders, are laid to rest. It's been an interesting day investigating crime, but now it's time to reflect on their primary goal: to do anything to advance the search for their killer. The silence of two little girls who were sometimes known to hitchhike is deafening. |

|

||||